Today was a sad day for women and people everywhere due to the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe V. Wade. This is an assault on bodily autonomy which will have negative long term consequences for women, girls, and all people with a uterus, not only in the U.S. but internationally. By reversing Roe V. Wade, the U.S. is signaling to the rest of the world that women’s rights, and indeed, the bodily rights of all people, can be rolled back with impunity. Justice Thomas has already stated that the Supreme Court should reconsider laws on the right to contraception, same sex relationships, and same sex marriages. The repercussions of these will be monumental, particularly for the security of women and LGBTQIA+ people. This ruling makes the U.S. a global outlier as more countries have been expanding laws on abortion in recent years rather than rolling them back. I am sure, like me, many of you feel angry, depressed, or numb, and while it is important to grieve this loss we must also stand up to this attack on our rights. Let’s pull together and take whatever action we can, by voting in the midterm elections, supporting NGOs working for women’s rights, signing petitions, participating in protests, and by never giving up!

Dr. Shirley Graham, Director, Gender Equality Initiative in International Affairs

Category: GEIA Article

Podcast launch by GEIA Student

Hearty congratulations to undergraduate Taylor Bloch who recently completed her final thesis and created this wonderful Spotify podcast, “Global Queery” that aims to create a queered and decolonized vision of peace and security by amplifying youth, BIPOC, and LGBTQ+ voices globally.

Please check out “Pale, Male and Yale: Diversifying international affairs and public policy curriculums” and listen to Taylor’s interview with Rachel Yakobashvili, a graduate student at the George Washington University, about diversifying and decolonizing international affairs and public policy curriculum and syllabi. In the conversation, they explore

who really is an “expert,” cishet white male-only syllabi, and how a lack of diversity in academics impacts our ability to be effective global citizens. Listen to this episode to learn how you can advocate for more diverse voices in your classrooms and decolonizing academia.

New Gender in IA Concentration for BA and BS programs

GEIA is excited to announce a new ‘Gender in International Affairs’ concentration for undergraduate students. This is the first time the Elliott School has offered this concentration. We have created this concentration to equip our next generation of international affairs leaders with gender expertise, which a rapidly expanding field of knowledge required by a growing number of government departments, think tanks, multilateral institutions, and INGOs.

This concentration will provide students with an opportunity to deepen their knowledge of international affairs analyzed through a feminist intersectional lens. For example, we now have overwhelming empirical evidence correlating women’s status in a country with its security, stability, and prosperity, the more gender equal a nation-state is, the less likely it is to use violence to resolve conflicts, which in turn has a positive impact on international security. To complete this concentration you will have to take two core courses [choosing from Masculinities in International Affairs; Women’s Rights and Gender Equality; Women in Global Politics] and take three additional courses, a full list is on our website. You can also add gender-related courses offered by other departments and programs at the George Washington University.

For more information and a complete list of courses send an email to baia@gwu.edu

Statement on the Draft Opinion on Overturning of Roe V Wade

By Dr. Shirley Graham, Director, Gender Equality Initiative in International Affairs, GW Elliott School of International Affairs.

GEIA condemns the draft opinion from the Supreme Court on the overturning of Roe V. Wade. Not only is it a violation of women’s human rights in the US but it also has serious implications for women’s rights globally. Nearly one in four women in the US will have an abortion. The World Health Organization recognizes abortion as an essential aspect of healthcare. And, the United Nation’s Beijing Platform for Action, a 12-step pathway to achieving gender equity globally, states that ‘the human rights of women include their right to have control over and decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health, free of coercion, discrimination and violence.’ In 2015, the United Nations developed the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) often referred to as the 2030 Agenda. These 17 goals are a pathway to protecting life on Earth. They include goals on access to clean water, renewable sources of energy, and quality education. The cross-cutting goal, the one that is necessary to achieve all the other goals, is women’s empowerment and gender equality. Why? Because the evidence-based data tells us that when women have access to resources and decision-making power it is not only better for them but also for their children, their families and their communities. For example, women politicians are more likely to advocate for maternity and paternity leave, affordable childcare, women’s access to equal pay, and social safety nets that protect the most vulnerable in society. When women have access to decision-making power, everyone is better off.

Women’s status in their country is an indicator of that country’s stability and prosperity. The erosion of women’s rights not only creates insecurity and harms women in their own country but it also erodes peace and security globally.

Women’s rights, and the rights of gender and sexual minorities, are being rolled back by authoritarian, rightwing, populist regimes in many countries, including Poland, Russia, Hungary, Brazil, Turkey and the Philippines. Fundamentalist and extremist groups and ideologies use women’s bodies to define the boundaries of their values and beliefs, whether they are in the US or Afghanistan, women are seen as the biological and cultural reproducers of national, religious and ethnic identity. That is why these groups fight to control women’s bodies.

On the fourth day of Donald Trump’s presidency in 2017 he signed the Mexico City protocol commonly known as the global gag rule. It stopped any USAID supported/funded clinics or medical centers in the global south from being able to provide, or even inform women about, abortions. It didn’t matter if these were girls or women who had been systematically raped by soldiers during war, or if they were carrying a fetus with a fatal abnormality, these women could not access the critical medical care they required. We know that a majority of Americans support women’s right to choose. But, we also know that the fact that a right has existed for almost 50 years does not guarantee its continuation.

What is to be done?

Time and time again it has been demonstrated that national women’s rights movements coming together with transnational feminist movements are the most powerful way to advocate for and protect women’s rights. In Colombia earlier this year the Green Wave Movement led to the legalization of abortion, this followed a wave of rights won by women in other Latin American countries such as Argentina and Mexico. Women in Ireland had travelled to the UK to access abortions for decades because the Irish State preferred to export ‘the problem’ rather than provide the healthcare women required. In 2018, women’s activism, inspired and supported by the global feminist movement, led to the Repeal of the 8th amendment, paving the way for the provision of safe, legal abortions.

If Roe V. Wade is overturned by the Supreme Court, women, and all people with a uterus in the US, will have lost their constitutional right to access abortions and to have sovereignty over their own bodies. Take action, raise your voice, vote in the midterm elections and demand women’s right to choose. Voting will not only protect rights domestically it will also ensure that the US provides strong leadership in the protection of women’s rights and human rights globally.

“What we see globally is that very often when right wing authoritarian regimes take power, one of the first things they do is push back women’s rights. It really raises the alarm bells in terms of the issue here in the U.S.”

– Dr. Shirley Graham in U.S. News & World Report “The U.S. Is Poised to Be a Global Outlier on Abortion.’

Dr. Shirley Graham on the Importance of Women’s History Month

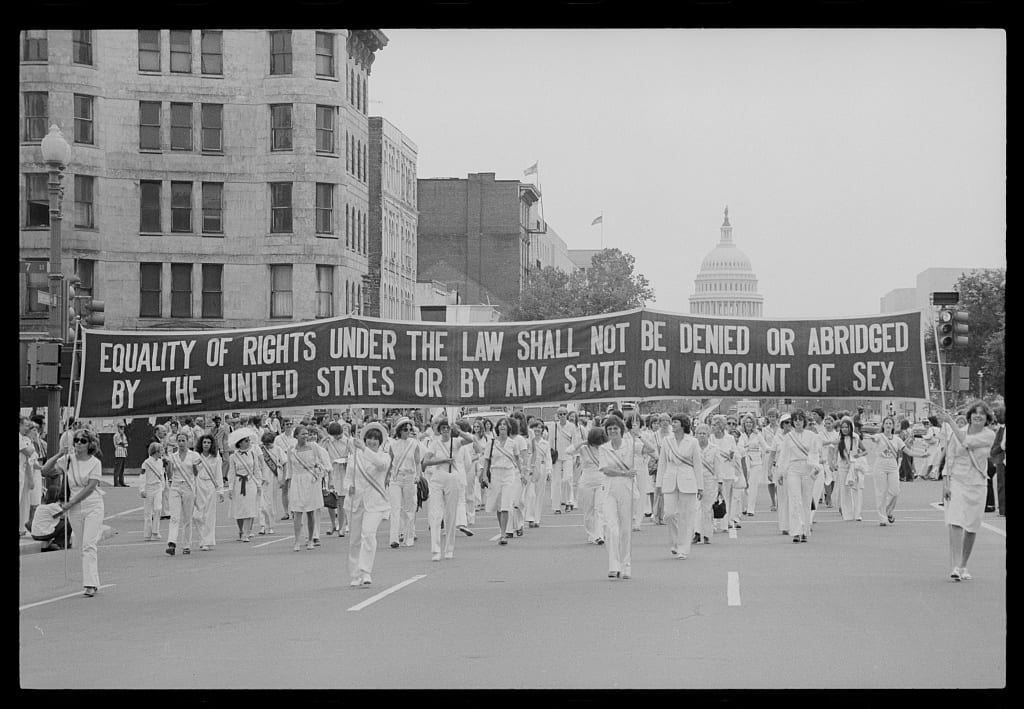

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

Why is women’s history month important? Because historically women have been written out of history. Men, and the performance of masculinities within the realm of militarism, violence, conflict, wars, and diplomacy have been the priority of most historians. We have heard a lot less about women’s roles in war, as strategists, spies, combatants, soldiers, nurses, cooks, and domestic workers, amongst others. Similarly, we do not know much about the many women who have brokered deals with local rebel groups facilitating the release of hostages, or who have played crucial roles in countering violent extremism, the women who have worked across political and religious divides to mobilize support for peace, and the women who have led processes to reintegrate former combatants into society as part of post-conflict reconciliation.

Women have been challenging this erasure of our multifarious roles in society for centuries, at least since the 15th century when Christine de Pizan wrote The Book of the City of Ladies and then later in the 18th century with Mary Wollstonecraft’s famous book, Vindication of the Rights of Women. Knowledge is power. As women were given access to education literacy rates improved and women began to write about their experiences, often anonymously to have their work accepted for publication.

Today, these views have changed but they have not been completely erased. Take the recent takeover of Afghanistan by the Taliban and how their first actions were to remove girls from school and ban women from accessing employment outside the home. This is a key tactic of extremist groups, they espouse misogynistic ideologies to deprive women of their economic, physical, and intellectual liberty. Demeaning any group creates stereotypes and the denial of that groups accomplishments and social value leads to discriminatory cultures and laws. Over time, this discrimination becomes institutionalized through the education and socialization of children. Any erasure of women from society violates our most basic human rights as set out in the UN Declaration of human rights (1948).

In fact it was women who insisted that the term ‘everyone’ rather than the personal pronoun ‘his’ was (mostly) used in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. And, similarly, it was the four women out of the 50 signatories to the UN Charter (1945) who argued for the inclusion of the word ‘women’ in the phrase ‘equal rights of men and women’. These women were joined by 15 other women from countries as diverse as China, the Soviet Union, France, Brazil, India, and the USA to create the UN Commission on the Status of Women in 1946. They came together from different religions, races, and cultures under the leadership of Danish diplomat Bodil Begtrup, another woman who few people have heard of, to gather data from across the world to assess women’s status in the home as well as in public life. They needed this evidence-base to argue for policies and laws to end women’s discrimination. As a result of the foundations of their early work we now have a global gender policy architecture in the UN and human rights treaties such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women that hold nation-states to account on gender inequities.

At the UN Women’s conference in Beijing in 1995, Hilary Clinton declared that ‘Women’s rights are human rights’ a statement that was considered radical for its time and which she was advised against saying. While progress on gender equality has been made since then we cannot take it for granted. Increasingly, right-wing populist leaders and groups are attacking women’s rights, and the very foundations of gender equality, for electoral mileage. In 2020, the UNDP published a Gender Social Norms Index report with the findings that almost 90 percent of people, both women and men, display ‘prejudiced sentiments towards women’ and the problem is getting worse.

Feminist researchers have now gathered ample data demonstrating the correlation between women’s status in society and a nation’s stability, security and prosperity. Countries with higher levels of gender equality are linked to good governance and are less likely to engage in violence either within their own borders or with neighboring countries. Yet, women still do not have full equal rights with men in any country today. In only 10 countries is there gender equality within the law: Belgium, France, Denmark, Latvia, Luxembourg, Sweden, Canada, Iceland, Portugal and Ireland.

A key role of feminist historians is researching women’s lives and bringing their achievements and stories back into our social consciousness. Women’s History Month provides us all with an opportunity to research, write about, share stories and raise awareness of the diversity of women’s lived experiences and the work that still remains to be done to bring about gender equality – raise your voice for women’s rights!

Join the Gender Equality Initiative in International Affairs and the D.C. Student Consortium on Women, Peace & Security to celebrate International Women’s Day on Tuesday 8 March in the City View room where we will be honoring Muqaddesa Yourish, a former minister in the Afghan government and the Elliott School’s Shapiro Professor. Register for DCSCWPS International Women’s Day Celebration

Index Launch Event Summary

Erin Cieraszynski, Research Assistant and Fellow

On April 14th, 2021, the Gender Equality Initiative in International Affairs (GEIA) proudly hosted the official launch of the GEIA Women’s Leadership Index at the Elliott School of International Affairs. This project has been in progress for over a year, led by visiting scholar Gwen Young and with support from student research assistants Erin Cieraszynski and Anuka Upadhye. At this event, aptly titled Women Leading Globally: Tracking Representation and Power in 2021 — Gwen Young and GEIA Director Shirley Graham discussed why this data is crucial with particular focus on women in national security.

The main question of the event was “why data?” In conclusion, the index is solutions oriented. It exists to measure, see change, and understand which levers need to be pushed to enact gender oriented policies. It helps us understand which strings of society we need to pull to change the way women are treated. Young explained simply that “we need to be able to measure where we are in order to get to where we want to be.”

More deeply, the index shows the relationship between different indicators and how they are all related. The 80 plus indicators spanning 75 countries cover 5 sectors of government, but mostly make up 3 categories: Pathways, Position, and Power. Pathways define how one gets into leadership — through education, equality clauses in the constitution, access to jobs, etc. Position outlines what the leadership positions are and if women occupy them. Power analyzes whether women can influence agenda setting and the extent to which their position allows them to make decisions over key institutions, such as budget control, and if they have veto power or control over the rule of law. While the compilation of these indicators paints a picture of each country, the index does not rank them from “best” to “worst.” Instead, the index categorizes each country into one of four sectors: balanced parity, siloed parity, flat parity, pursuing parity. By doing this, the index effectively is able to compare and contrast each country as it stands and demands parity across the board, not just those in the lowest tier. For example, the United States is parallel to Nigeria and South Korea in the flat parity section.

In looking at the indicators and country’s statuses, it is obvious that there are a few key takeaways. The first is that education matters — not just formal education — but informal training and trade schools as well. The second finds that part time work enables more women to lead, as many women are in part time positions for most of their career. With options such as subsidized childcare and improved education, this part time work becomes more viable. The third takeaway determines that public administration is the closest sector to parity than anywhere else, but only in certain topics. More women are needed in the finance, defense, and infrastructure fields. The final takeaway is that perception matters — meaning how the media portrays women and how people talk about women’s issues in the country. This changes the vision of what good and expected leadership looks like. Overall, women are linked to good governance and should be in decision making positions to improve the overall health of a country’s institutions.

Within national security these numbers are especially important as women are severely underrepresented in this sector. However due to strict security and confidentiality rules, this data is not the easiest to obtain. In general, the link between women in leadership positions and levels of violence are inextricably linked. The more gender equal a country, the more stable, secure and prosperous it is, therefore, when there are more women in positions of power a country is more likely to be peaceful. Women need to be not only at the table, but also need to be the ones signing peace treaties, advocating for negotiations, and participating actively in resolution processes.

There are many steps to move forward with this index and gaps to fill. It is a consistently evolving framework which always has room for improvement. For example, it needs to expand to covering more than 75 countries and will benefit from new data about the judicial branch and workforce numbers related to the COVID-19 pandemic. These gaps create many opportunities for faculty and student engagement alike, and we are glad the index has the support from the Elliott School to allow it room to continue to grow and improve.

The event concluded with a special appearance from the Dean of the Elliott School of International Affairs, Dr. Alyssa Ayres. With the Dean’s encouraging comments of support, it is obvious that the GEIA Women’s Leadership index is just getting started at its new home and will have a positive impact on the community for years to come.

Introducing the GEIA Women’s Leadership Index and Process

Erin Cieraszynski, Research Assistant and Fellow

The launch of the GEIA Women’s Leadership Index (GEIA WLI) at the Elliott School presents an opportunity to expand what we know about women’s positions, power, and pathways to leadership. This compilation of facts and figures identifies specific ways in which a particular country can move towards gender parity compared to where they currently stand. Previously at the Wilson Center as a part of the Women in Public Service Project, the index was revolutionary in the sense that it was the world’s first and most comprehensive data set detailing the status of women in the public service sphere. At the Elliott School, the index carries on this prestige and utility while offering the GW community a chance to get involved.

As a research assistant over the past year, I’ve had the great privilege of working with GEIA Visiting Scholar, Gwen Young, on crafting a unique website for the index and contributing to the data updating process. The initial index was launched at the Wilson Center in 2017 and used data from a combination of sources such as the World Bank, the World Values Survey, the Inter-Parliamentary Union, to name a few. Once the project was revamped at the Elliott School in early 2020, one of the main priorities was making sure it reflected relevant and up to date data. For me, this process involved piecing through each of the 80 plus indicators and tracking to see if there was newer data available. The new data was then uploaded to the site, making the index reflective of the current landscape. Our vision is to replicate this process every few years in order to keep the index as relevant and useful as possible. Along with this data update, the country composite scores will be recalculated and reevaluated to measure each country’s progress over time.

The GEIA Women’s Leadership Index will be a valuable tool for the GW community in both terms of using its findings and contributing to them. The index provides 80 plus indicators all in one place, spanning from the number of women in parliaments across the globe to the average paid maternity leave length in each country. Students and faculty alike can use this collection of data for research purposes in papers, projects, and more. On the other hand, GW students and faculty can also help compile and update this data as new numbers become available. While the index currently has a wide range, there are many other indicators that could be added to it. In a post- pandemic world, tracking women’s access to and power within public service positions will become even more critical. The GW community will be able to help add these new indicators and adapt the index to reflect the global impact of COVID-19. In addition, contributors are invited to share their findings and insights in blogs or reports that live on the index’s site. With the GEIA Women’s Leadership Index as an integral tool that will help the world reach gender parity, we hope GW students and faculty can benefit from and progress the index for years to come. For more information, join our launch event on April 14th, 2021 at 12pm ET and check out the index itself here.

A MEMO to the Elliott School of International Affairs’ Council on Diversity and Inclusion

FROM: Tyler Burrell

RE: Lack of Disability Diversity in the Elliott School Curriculum

BACKGROUND:

While the Elliott School does a commendable job of integrating some aspects of diversity (such as gender) into its curriculum, the lack of studies on disability and International Affairs (IA) is disheartening. According to the World Health Organization, one billion people – or 15% of the world’s population – experience some form of disability. Because of this, the disability community is often referred to as the largest minority in the world. Disability does not discriminate, and thus directly intersects with gender, race, socioeconomic status, and all manners of identity. The complex intersectional nature of disability causes it to have a significant impact on IA, including the studies of development, humanitarian aid, food security, public health, economics, security, war, and conflict resolution. The Elliott School must assume its responsibility to teach its students how disability diversifies and intersects with these critical policy areas to fully educate and prepare them for effective careers in IA. Currently, the Elliott School of International Affairs (ESIA) lacks any official policies regarding disability in coursework. ESIA ensures accessibility for disabled students in the program, but not the intersectional inclusion of disability within IA. The inclusion of disability studies in the Elliott School’s curriculum should be a priority because true diversity cannot exist without disability.

POLICY OPTIONS:

- Invite more disabled and disability-specialist professors and guest speakersto the Elliott School to bolster diversity. These professionals’ perspectives are vital to enhancing the program and will be able to shape and guide how ESIA includes disability in its curriculum.

- Integrate disability modules into pre-existing courses. General and specialized courses alike should include modules on disability in IA.

- Create specialized courses focused on the extensive impacts of disability on IA. Similar to the courses dedicated to gender, the Elliott School should form courses dedicated to educating students about the intersections of disability within various IA sectors.

RECOMMENDATION:

The Elliot School should pursue the adoption of policy options 1 and 2: inviting those who are disabled or specialize in disability and IA to the Elliott School, and integrating disability modules into pre-existing courses. Though the development of specialized courses on disability and IA should be pursued in the long-term, integrating disability modules into pre-existing courses is a cost-effective first step.

Adopting a U.S. Feminist Foreign Policy: How the Biden Administration Can Stand with LGBTQ+ Survivors of Violence Seeking Asylum

By Alice Schyllander

History will be made on January 20th as Kamala Harris is sworn in as the first woman of color Vice President of the United States. Senator Kamala Harris is the nation’s first woman, first Black and first South Asian Vice President breaking many barriers. The inauguration of the Biden-Harris Administration represents an important opportunity milestone in U.S. history, and could represent an opportunity for global gender equality activists to push for the U.S. to strengthen its policies on gender abroad. This administration has already proposed an impressive slate of both domestic and foreign policies to address racial justice, gender equality, and LGBTQ+ rights, it is very possible that activists have the opportunity to push for this administration to adopt a more transformative approach to foreign policy. A Feminist Foreign Policy (FFP) has the power to transform U.S. foreign policy priorities to center those who have been most marginalized under the Trump Administration. A FFP would seek to center the experiences of communities historically marginalized by current and past U.S. foreign policies using a trauma-informed lens in the policy creation process. Current U.S. immigration policies force many asylum seekers to experience trauma while attempting to seek asylum, a community that by its very definition has undergone significant traumatic experiences. This is especially true of Central American LGBTQ+ asylum seekers who experience disproportionate harm in their countries of origin, in-transit through Mexico, and while undergoing the U.S. asylum process. A U.S. feminist foreign policy can transform the policy priorities of U.S. immigration policy to center the needs of LGBTQ+ survivors of violence who are seeking asylum status.

LGBTQ+ people in Northern Triangle Countries (Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras) experience high levels of violence and persecution. It is challenging to obtain accurate data on the levels of violence experienced by LGBTQ+ people in these countries due to lack of official data collection on this issue. However, several NGOs and international organizations have collected data on this topic. In a 2016 study, Northern Triangle countries were considered one of the most dangerous regions in the world for trans women. The high rates of violence are exacerbated by the lack of accountability for the perpetrators of violence. Cattrachas, a Honduran LGBTQ+ rights nonprofit, found in a study that of the 225 violent deaths of LGBTQ+ people recorded during 2008 to 2015 in Northern Triangle countries only 13 had resulted in a conviction. Many LGBTQ+ people in Northern Triangle countries choose to flee due to the high rates of violence and persecution. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 88% of LGBTQ+ asylum seekers and refugees from Northern Triangle Countries have experienced gender-based violence in their country of origin. Many LGBTQ+ people are left only with the option to escape in order to maintain their lives and physical integrity.

LGBTQ+ asylum seekers have been harmed by the Migrant Protection Protocols (the “Remain in Mexico” Policy) and the U.S.-Guatemala Asylum Cooperative Agreement (the Safe Third Country Agreement) enacted under the Trump Administration. The Remain in Mexico policy requires asylum seekers who have appeared at a port of entry at the U.S. Southern border to wait in Mexico while their case is being processed through the U.S. immigration system, instead of waiting in the U.S. as before. Vulnerable populations are supposed to be exempt from the Remain in Mexico policy, but LGBTQ+ asylum seekers are not exempt from the program. The U.S.-Guatemala Asylum Cooperative Agreement is a treaty that allows U.S. immigration officials to send Honduran and Salvadoran asylum seekers to pursue an asylum case in Guatemala, not allowing their asylum claims to be heard in U.S. immigration courts. LGBTQ+ asylum seekers are also not exempt from being sent to Guatemala, despite a lack of anti-discrimination policies for LGBTQ+ people and a limited capacity for a full and fair asylum procedure in Guatemala. Both policies return LGBTQ+ asylum seekers back to the same conditions of persecution and violence they were escaping in their home countries subjected Central American LGBTQ+ asylum seekers to additional trauma.

It is difficult to estimate exactly how many LGBTQ+ asylum seekers from Northern Triangle countries have been directly impacted by the Remain in Mexico policy. Cases from Northern Triangle countries made up more than half of the total 4,385 asylum claims for anti-LGBT persecution between January 2007 and November 2017 according to the US Citizenship and Immigration Services. It is difficult to estimate how many LGBTQ+ asylum seekers experienced violence or persecution while being forced to wait for an indefinite amount of time in Mexico. There is data on the rates of gender-based violence against LGBTQ+ asylum seekers on their journey through Mexico. In 2016 the UNHCR found that two-thirds of LGBTQ+ asylum seekers and refugees from Northern Triangle Countries reported experiencing sexual and gender-based violence in Mexico after they crossed the border at a blind spot. The risk for violence against LGBTQ+ asylum seekers has caused many Congressional lawmakers to inquire about the Remain in Mexico policy. Forty Congressional lawmakers have sent two letters to the Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties and the Inspector General at the Department of Homeland Security asking for clarifications about the Remain in Mexico policy for LGBTQ+ asylum seekers. In the second letter, congressional lawmakers included that there have been 340 public reports of rape, kidnapping, torture, and violent attacks against asylum seekers in the Remain in Mexico program from January to November 2019.

It is challenging to determine the level of harm the U.S.-Guatemala Asylum Cooperative agreement has caused LGBTQ+ asylum seekers due to a lack of data collection. Transfers are currently suspended due to the public health emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic beginning in March 2020. There were 939 Honduran and Salvadoran asylum seekers transferred to Guatemala under the US-Guatemala ACA between November 21, 2019 and March 16, 2020. Only 2% of the total number of transferees have applied for asylum in Guatemala. There have been no attempts by the Guatemalan government to work with LGBTQ+ rights organizations to coordinate and to provide information about available resources to LGBTQ+ asylum seekers transferred under this agreement.

When LGBTQ+ asylum seekers arrive at the U.S.-Mexico border nearly all of them have experienced gender-based violence and most are also recent survivors of violence. The policies of the Remain in Mexico policy and the U.S.-Guatemala Asylum Cooperative Agreement subject LGBTQ+ asylum seekers to more trauma by sending them back to conditions of violence, poverty, and persecution. The Biden-Harris Administration has the opportunity to create a humane asylum process for LGBTQ+ asylum seekers by ending both policies immediately upon entering office. A U.S. FFP can have a transformative impact on U.S. foreign policy priorities, by creating a humane and dignified immigration process that takes a trauma-informed approach.

Alice Schyllander is a second-year graduate student at the George Washington University in the Elliott School of International Affairs in the Master of Arts in International Affairs program concentrating in Global Gender Policy and International Law & Organizations. Alice has focused her studies and professional work on addressing issues of gender equality, gender-based violence, immigrant rights, refugee rights, and LGBTQ+ rights globally with a regional interest in Latin America. She has worked previously at the Interfaith Council for Peace and Justice, Planned Parenthood Action Fund, the Tahirih Justice Center, Vital Voices Global Partnership, and the Elliott School of International Affairs.

GEIA Book Launch Roundtable – The Gender and Security Agenda: Strategies for the 21st Century

By Nina Plateroti

In October 2020, I had the great opportunity to attend a book launch hosted by Dr. Shirley Graham, Director of the Gender Equality Initiative in International Affairs (GEIA) for “The Gender and Security Agenda: Strategies for the 21st Century”. This book examines the gender dimensions of a wide array of national and international security challenges, exploring gender dynamics in ten issue areas in both the traditional and human security sub-fields: armed conflict, post-conflict, terrorism, military organizations, movement of people, development, environment, humanitarian emergencies, human rights, and governance. These examinations show how gender affects security and how security problems affect gender issues. Each chapter examines a common set of key factors across these issue areas: obstacles to progress, drivers of progress, and long-term strategies for progress in the 21st century. The volume develops key scholarship on the gender dimensions of security challenges, providing a foundation for improved strategies and policy directions going forward. The lesson to be drawn from this study is clear: if scholars, policymakers, and citizens care about these issues, then they need to think about both security and gender.

The books’ co-editors Dr. Chantal de Jonge Oudraat, President of Women in International Security (WIIS), and Dr. Michael E. Brown, Professor at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs, set out why they had published this book at this time. Dr. Chantal de Jonge Oudraat described how she had become, “…very frustrated with the framing of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda as a women’s agenda.” This book argues for a broader gender perspective rather than a woman’s perspective when discussing issues of gender and security, describing the importance of transforming structural and systemic inequalities rather than depending on rhetoric to bring about change. In her remarks, Dr. de Jonge Oudraat made it a point to emphasize the fact that women’s rights and human rights are not two separate entities to be broken up into two separate discussions stating, “… [women’s rights and human rights] are universal – it is not that you can pick and choose about human rights or women’s rights.” This book illustrates the strong correlation between gender inequality on the one hand and the onset of violent conflict and instability on the other, solidifying the interconnected nature of women’s rights and human rights.

In his remarks, Dr. Michael E. Brown argued for the expansion of the gender perspective in security policy, acknowledging the progress that has been made and emphasizing all that still needs to be done. Dr. Brown stated, “We are talking about changing the most deeply entrenched, institutionalized, pervasive and powerful structures in human affairs – patriarchies,” pointing to the fact that in the last 25 years there have only been two major articles in the Journal of International Security published on gender issues. Dr. Brown made clear how essential it is that agendas that started as the agendas of feminists and gender scholars become the agendas of all security scholars, focusing much of their work on the inherent connection between gender and security.

The conversation with co-authors Corey Levine, Anne Marie Goetz, and Ellen Harding discussed the obstacles to progress, the drivers of progress, and the long-term strategies for progress in the 21st century. Corey Levine, a Human Rights & Peacebuilding Policy Expert, examined how human rights – both as a concept and a series of laws – “… has used an equality model that focuses on the individual and has ignored the structural discrimination and disadvantages that are experienced by women and girls because of their gender.” Levine touched on the fact that there are customs and traditions so entrenched in societies the world over that they act as some of the most powerful obstacles to progress, and even in the relatively modern and continually advancing field of human rights, these obstacles prove formidable. As her discussion on the evolution of human rights and security brought us closer to the present day, Levine discussed how we now see an emphasis on women’s participation in national militaries and multilateral peacekeeping missions as an integral part of the Women, Peace and Security agenda. Levine stated that “This is in keeping with a shift away from the human security centered approach which put human rights and human development at the forefront [of US foreign policy],” during the 1990s. She discussed how since the turn of the century brought about intense focus on counterterrorism efforts as a result of 9/11, the stringent counterterrorism laws and regulations put in place to prevent money laundering to terrorist groups have negatively impacted the ability of local women’s groups to access aid and developmental assistance, particularly in countries like Iraq and Syria. Unfortunately, this is a prime example of how the emphasis on militarization and counterterrorism has had the twin effect of rendering women’s rights invisible, while, at the same time, amplifying abuses on the basis of gender. Through her discussion, it becomes increasingly clear that, even when unintended, changes in security policy will undoubtedly have consequences on gender equality efforts and regional stability as a whole. As Levine aptly put it, “…next to biological reproduction, war is the most gendered of all human activities.”

Dr. Anne Marie Goetz, a Clinical Professor at the New York University, focused her remarks on the liberal peacebuilding approach that the Women, Peace and Security Agenda has found a home in, although not necessarily a secure home. Dr. Goetz observed three trends away from the liberal peacebuilding approach: first, the backlash against liberal norms that is coming from some of the most affluent democracies that promoted these norms in the first place; second, a similar shift towards illiberalism from extremely important influential mid-sized regional powers such as Brazil, India, and Nigeria; third, the growing authority of China as a provider of foreign assistance, influencing small, conflict-affected states in its sphere. Interestingly enough, misogyny seems to be at the center of the promotion of these trends and while the liberal model created the space for the inclusion of Women, Peace and Security, Dr. Goetz notes that “…it did so belatedly and imperfectly.”

Dr. Ellen Harding, a Senior Fellow at WIIS, brought the conversation full circle by highlighting some of the obstacles women continue to face in joining the military. Dr. Harding stated that “…one of the key findings is that military organizations are quintessentially masculine constructs that are built on very traditional and highly dichotomous notions of masculine and feminine gender norms. Specifically, the notion of men as protectors and women as the protected and that physical strength is essential to success on the battlefield.” In this prevalent construct, there is no room for women except for as caregivers and in administrative and support roles. Often, the men who run the military buy into these constructs and, “…individual and institutional identity is threatened by women’s inclusion.” This is not to mention that laws in many countries continue to exclude women’s access to military jobs and their paid maternity and family leave programs remain limited, causing women to leave the military at high rates. Dr. Harding stated that, “When change has occurred, it has been driven by necessity and not necessarily by changing liberal social norms and certainly not by progressive views inside the military themself.” However, women’s increased participation in the military and their increased access to education and training has proved invaluable on the modern battlefield, pointing to just one aspect of the importance of women’s inclusion in the military. Dr. Harding’s remarks serve to highlight the inherent connection between gender and the most traditional sector of security – the military.

The book launch ended with a series of questions from the audience, ranging from topics such as how educators can aid in gender mainstreaming on the academic front to the drivers of progress in various gender equality initiatives and undertakings. This question-and-answer section was extremely insightful, providing audience members with food for thought and concrete ways we as students, educators, and advocates can make a difference. As a student at GW studying international affairs, I found Dr. Browns’ answer on how one can teach international affairs and security in a way that helps the cause particularly interesting and truly exciting. Dr. Brown stated that, “One key step is to have courses that cover a wide range of issues…the other part of it is to mainstream gender in our introductory and survey courses, as well…we have to be careful to not just have an hour or a week on gender and to check off the box and say, ‘Well, we did that,’ but actually to integrate it into the course as a whole.” Dr. Browns’ discussion on how he does this in his courses and how many GW programs work to achieve this imperative task made me eager for all that my education has in store. As the conversation came to a close, Dr. Brown made a final comment on the GEIA being exemplary amongst universities in educating future generations of leaders on gender in international affairs. He highlighted the amazing work it conducts under the leadership of Dr. Shirley Graham, imploring all invested in this work to look towards the comprehensive programs and courses offered by the GEIA.

As an undergraduate student committed to dedicating my career to the advancement of women’s rights, this conversation introduced me to nuances within the Women, Peace and Security agenda that I had not previously considered and left me with a deeper understanding of the real structural changes that are needed to make progress in the realm of gender and security. Structural change is necessary, not only in how the security field views the Women, Peace and Security agenda, but in how all sectors of the security profession work together – not as their own silos, but as organizations that are aware of the interconnectivity of their imperative work. Their efforts cannot be complete without cross-organizational collaboration and the fundamental understanding that the gender perspective is a security perspective that affects all of humanity, not just women.

Nina Plateroti is a freshman at the George Washington University in the Elliott School of International Affairs. She is working towards a double major in international affairs and political science, with a minor in women, gender and sexuality studies. She is a Freshman Representative for GW Leading Women of Tomorrow and serves as Secretary to her local League of Women Voters.